December 19, 2024

The behavior of Brazilians in relation to reading was the theme of the survey Retratos da Leitura, recently published by Pro-Book Institute. The survey showed that most Brazilians (53%) had not read even part of a book in the three months prior to the question, which is considered a non-reading profile. This is the worst result since 2007, when the survey began. The project Learning: Inside and Outside School, currently being implemented by Labedu in 217 municipalities in Maranhão in partnership with the state department of Education (Seduc/MA), aims to address this reality, strengthening the reading skills of educators and children from zero to five years old.

We spoke with Cecília Diniz, a researcher in Sociology of Education and trainer at Labedu, to understand how the project's methodology and the articulation of actions in partnership with the public authorities contribute to promoting reading in territories often marked by social inequality.

Looking at the survey results, the data on the influence and development of readers is quite striking. When comparing those considered readers, we see a significant difference of almost 20 percentage points: 46% of children who read had someone read to them, while only 28% of non-readers had the same. It seems somewhat obvious to say that the habit of a caregiver reading to a child will have a positive impact on their development as a reader, but how can schools influence this process at home?

When we started implementing Aprender in 2019, we saw that reading to children was not a habit in Early Childhood Education, which is the focus of the project. It happened, but it was very rare. They had very small collections, or even where there were more books, they were not read to the children. They did not understand that this was something important to do, or they told stories, which is different from reading. And even then, it was not part of their daily routine. Since then, the project's work has focused on strengthening the practice of daily reading aloud by the teacher, promoting a consistent approach between children and books. If all teachers read to children daily, it would already be a huge step forward!

We also work with principals to strengthen and implement projects that promote book lending so that children can take copies home. So, even if they don't have books at home due to lack of resources, the Early Childhood Education institution lends them so that they can spend time with their families. In this way, we help to strengthen the partnership between the institution and families.

Labedu's work is very much based on this binomial, right? It's the motto "every child can learn and every adult can educate", it's the name of the project itself "inside and outside of school". It's very important to take care of these two aspects. Even though our direct relationship is with Early Childhood Education, we are thinking of actions that can resonate in the family, to create a partnership between families and Early Childhood Education.

How are teacher training programs designed to ensure not only the presence of reading, but also qualified reading? How do we train those who train readers?

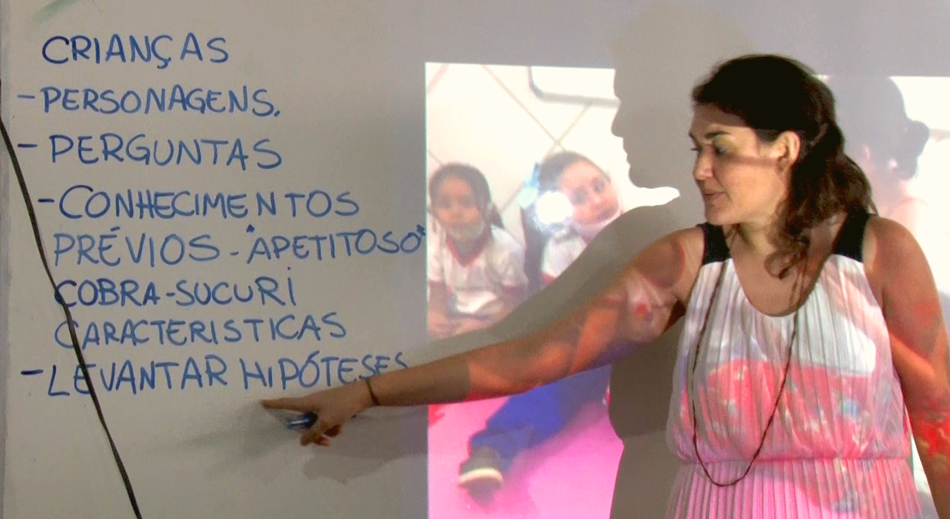

An important piece of information for understanding this issue emerged during the assessment of the territory. As we saw, the teachers and coordinators themselves were often not readers. They also did not have this reading training, which is evident in the results of Retratos da Leitura. So, in the first phase of the project, we did a very important job of training the education professionals who would read to the children to read. Because the person who is going to read to the children needs to agree that this is important, that it is not an extra activity to be done when other resources have run out, or when there is time left over.

So, we worked to train the coordinators so that they could train the teachers. We worked mainly on literary reading, which is an experience of contact with the text, of remembering things, about what you feel, what you think based on that text... And that's where the issue of inequality of access comes in. Someone who has not had a good reading education will have a hard time training readers, whether their children or their students. The result of this work with the educators was a great appreciation of reading. After reading a short story during the training, many would come back and say that they had read the whole book afterwards, for example.

And teacher training is done with adult literature, right?

Exactly, so that they can become readers, so that they can value it and put it into practice. Because we believe that it is difficult for someone who is not a reader, who does not see the value in it because they do not have this prior experience, to be able to mediate reading well, to be able to understand how transformative this is, so that they can, in fact, fight to have reading every day in the institution where they work.

Why is telling a story not the same thing as reading to children?

In the beginning, we often saw the two things being confused. And for many reasons. Sometimes it was due to a lack of access to books, or because they thought that young children wouldn't pay attention when reading, or even because they believed that storytelling would get their children's attention more. It also happened a lot that teachers would do dramatizations, like making puppets of the characters in the story, or dressing up to act out the story. The problem is that all of this ends up complicating the activity. The time it takes to make the puppets or set up the sets doesn't make it feasible to do it every day. You're going to do this once a month, right? As for reading, all you need is a good book. You just need to read it beforehand, prepare yourself, and read it to the children.

Furthermore, when reading, you are putting children in contact with written language. The organization of written text is different, even when it is read aloud. And it also provides interaction with the book as an object. If we want children to be interested in reading, they need to be in contact with this object, the book. It is not just the text, just the story, it is the illustrations, the interactions that many authors make between the illustration and the text... Looking at all these elements develops other reading skills, which storytelling does not favor.

I'm not saying that storytelling isn't important, but what we need to ensure every day is reading texts. It's about letting children handle books, while teaching them how to handle them carefully. Therefore, if we want them to be enchanted by books, they need to be able to handle them, interact with them, with an adult there guiding them and reading to them. All of this has been part of our training.

And what is the role of project monitoring, of this monitoring that Labedu does to adjust training?

It is essential. It is not just about providing training and thinking that the mission is accomplished. We go into the field to observe teachers reading, how they are doing it. If they have been able to read or are still telling a story, or retelling the story with the book in their hands. How do I guide this teacher? It is the monitoring work that feeds back into the training. With this, we can see what the challenges are in practice and adjust them.

Returning to the issue of reader training, it benefits not only learning, but the full development of children, right?

You brought up something very, very important. There is a mistaken idea that you read to teach children something. In our training, we work on the idea that we read so that children can experience books and encounter texts. In Early Childhood Education, we read to broaden children's understanding of the world, their vocabulary, and their relationship with language.

In the following stages of school life, everything will depend on this understanding of reading that is built in Early Childhood Education, which is not about reading just to decode. It is not about reading to understand letters and form words. It is about reading in the sense of reading the world itself, of understanding and relating to that text, of creating meaning for what is being said.

The research indicates a peak in the proportion of readers between the ages of 11 and 13, and then this number progressively drops, meaning that Brazilians stop reading throughout their lives. Why do you think this happens?

With frequent reading, whether done or recommended by teachers, it is possible to build a reading community in Early Childhood Education and Elementary School. When we read a book and suggest that everyone talk about it, about what they felt, what they thought, what they remembered… I think that in adulthood we may become discouraged from reading and give up due to the lack of participation in a community of readers. Because having someone to talk to and share books with is very important. If people are talking about a certain book, I feel like reading. Schools can build this, right? Because you read the same text to all the children and they can comment on the reading, or when the children are a little older they start to recommend the books they have read. So schools also have an important role in helping to build this reading community. The question is whether or not they are actually being this community, right? But they also have a role in building this reading environment.

Find out more:

Article presents experience report on Labedu project in Maranhão

Access the 6th edition of Portraits of Reading in Brazil here